Douglas Messerli [USA]

a

homespun american proust

James Agee and Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: Three Tenant

Familes

(Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1941)

William Christenberry, Foreword by Elizabeth Broun, with Essays by Walter

Hopps, Andy

Grundberg, and Howard N. Fox (New York: Aperture/with the

Smithsonian American Art

Museum, 2006)

Passing Time: The Art of William Christenberry, Smithsonian American Art Museum, July 4,

2006-July 4, 2007

William Christenberry: Photographs, 1961-2007, Aperture Gallery, July 6-August 17, 2006

Howard N. Fox, lecture at the

Smithsonian American Art Museum, July 22, 2006

Richard B. Woodward, “Country

Roads,” New York Times Book Review, September

3, 2006

William Christenberry,

lecture, UCLA Hammer Museum, November 30, 2006

On July 22, 2006—during a trip to

Washington, D.C. to celebrate the 90th birthday of my companion’s

father—Howard lectured on the occasion of “Passing Time: The Art of William

Christenberry” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Howard had also

contributed an essay to the recent Aperture publication, William Christenberry. Although we intended to arrive early to meet

the Christenberrys for a tour beforehand, D.C. traffic prevented him from

joining them—he had to preview the sound and projection systems before his

lecture—and I toured the show with Bill and Sandy without him.

We had known Bill and Sandy for some years going back to our

life in that city. Howard reminds me that our first dinner of spaghetti alla

carbonara was shared with them at Pettitos on Connecticut Avenue. I also recall

an afternoon in their home and a visit to his studio with Howard, which I will

discuss later in this brief essay.

The tour of his new show was fascinating

to me not only because I enjoy Christenberry’s art, of which this show

presented a good selection, but also because of the artist’s own observations

about his art. I recognize that most critics detest just such heavily “guided”

viewings; but I love them, if only because it is at these times when one can

truly get to know the artist—or at least get to know what the artist feels is

most important about his art. Bill is a laconic southerner, and I don’t believe

that he offered much information about his work that hasn’t previously been

published, but the tone of his

comments and the focus of his

observations were significant, if only in his reiteration of his major

concerns. What a pleasant afternoon: a guided tour by the artist followed by my

friend’s lecture! The tour of his new show was fascinating

to me not only because I enjoy Christenberry’s art, of which this show

presented a good selection, but also because of the artist’s own observations

about his art. I recognize that most critics detest just such heavily “guided”

viewings; but I love them, if only because it is at these times when one can

truly get to know the artist—or at least get to know what the artist feels is

most important about his art. Bill is a laconic southerner, and I don’t believe

that he offered much information about his work that hasn’t previously been

published, but the tone of his

comments and the focus of his

observations were significant, if only in his reiteration of his major

concerns. What a pleasant afternoon: a guided tour by the artist followed by my

friend’s lecture!

It may appear, accordingly, that I might have little to

observe other than sharing these pleasant memories. Given that one of

Christenberry’s major concerns is the role of memory, that may not be a bad way

to approach the assemblage of paintings, photographs, sculptures and mixed-media

works collected in “Passing Time.” What do we remember, and why? The numerous

old houses, sheds, barns, roads, churches, road signs, graves and

grave-markers, and other representations of his native Hale County, Alabama—a

region also explored in the photographs of Walker Evans and writings of James

Agee in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men—seem

to call up Christenberry’s youth or a time before his youth, when these same

buildings and objects, many now in decay, actively housed the activities of

living beings. And in that sense, there is a bit of nostalgia in the beautiful

world he presents, a beauty that, perhaps, illuminates the lives once involved

with these places and things. As Walter Hopps writes in his short essay to the

Aperture book: “Without its ever being maudlin or sentimental, there is a

belief in human goodness and redemption—in virtue and hard work and effort,

however tattered.”

Howard Fox reiterates these concerns in his essay, “An Elegiac

Vision”:

He characteristically depicts in all of his

art—photographs, paintings,

sculptures, drawings—the most intimate aspects of

people’s daily

human existence: the doorways through which they

enter and leave

in the course of their workaday routines; the

windows through which

they gaze out or peer in; their front and back

yards; the sheds where

they store their tools, their forgotten belongings,

and maybe their

secret things; the calendars and diaries wherein

they mark the passage

of time; even the humble objects used to mark their

graves.

Christenberry’s depiction of this everyday Alabama world,

however, often appears to be one of complete objectivity. As Fox points out,

these places and objects, particularly in the mature work, are nearly all

bereft of people. It is as if they are sensed only “by their absence.” The

riotous force of nature, indeed, has taken over, and, in that sense—and despite

the “goodness and redemption” that once existed in these places and was

represented by the objects, there is a sense of total objectivity in his work.

As Richard B. Woodward observed in his New

York Times Book Review essay on the book, William Christenberry:

The kudzu devouring a vacant cabin in a 2004

photograph is a science

fiction monster that can turn anything into a Chia

Pet. Neither good

nor evil, the vine is simply a nuisance of life in

this part of the country.

Christenberry’s focus on the habitats and hangouts of

the poor, blacks

and whites, is similarly nonjudgmental. These places

weren’t constructed

to last for the ages and aren’t likely to be missed,

except by those

who filled them for a few years or decades. Still, he

treats them with

respect, charting their alterations and passings.

Paying careful attention

surroundings that would otherwise be forgotten or

unremarked upon

can be its own political statement.

Accordingly, it appears, it is

the attention to these places and things, the importance the artist himself has

put upon them and the memories through which he has viewed them that rewards

any value to his subjects.

Indeed, Christenberry further extends these issues of memory

with own reconstructions of various places and objects, most notably the

1974-75 sculpture of Sprott Church (surrounded on its pedestal by “real”

Alabama clay)—a “reconstruction” of the 1971 photograph, an image presented again

in photographs of 1981 and 1990 (the last of which reveals the removal of the

church’s two steeples) and the 2005 “memory” reconstruction (titled “Sprott

Church [Memory]”) that in its ghostlike white wax-covered rendition appears

like something out of a dream. Similarly, the “Green Warehouse,” photographed

18 times over a period from 1973-2004, is remembered in his 1978-79 sculptural

reconstruction of the 1998 painting “Green Warehouse.” Combined with his

several “Southern Monuments,” which read almost like surrealistic dreamscapes,

his patchwork house, and various “dream buildings,” these works call up issues

surrounding memory and the dreams memories invoke. His “Alabama Box” contains

works by the artist

depicting his native landscape as well as

objects and even soil from that state, a work which may remind one—in the art

historical context—of the dream boxes of Joseph Cornell, while recalling—from a

more populist perspective—Jem Finch’s treasure box (in To Kill a Mockingbird by fellow Alabamian Harper Lee) filled with

hard-carved objects found in the knot of a tree. Christenberry’s art carries

with it, accordingly, a sense of totemism, an almost mystical kinship with the

group of southern individuals whose structures and objects these works of art

symbolize.

What has generally been described as the “dark side” or the

“underbelly” of this world is Christenberry’s obsession with The Klan. Some

photographs call up Christenberry’s personal encounters with the Klan. “The

Klub” for example is a photograph of a small bar in Uniontown where, so Bill

described the incident to me, he had stopped for a drink. But upon entering the

building he’d gotten a strange feeling about its inhabitants, and he quickly

turned to leave, observing several individuals gathering near the doorway. “It

dawned on me, suddenly, the existence of the K in the word Klub. It’s a good

thing I left as quickly as I’d entered the place, and my car was tagged with

Tennessee license plates.” Fox relates Cristenberry’s first engagement with the

Klan in 1960, when he attended, “out of curiosity,” a Klan meeting in the

Tuscaloosa County Courthouse. “Or at least he planned to: ascending the stairs,

Christenberry was stopped dead in his tracks by the presence of a Klansman in

full regalia, whose menacing eyes glaring through the slits frightened him off

in a rush down the stairs.”

Howard also recounts his first viewing of the mysterious “Klan

Room” in Christenberry’s studio, a room separated from the rest of his studio

that looked like a padlocked storage area, a room revealed to very few

individuals. I was with Howard on that day in 1979:

For the few to whom Christenberry did reveal this

secret place,

the experience was eerie, disturbing, and

spellbinding. It was pure

theater. The door opened into a claustrophobic space

flooded with

bloodred light and as crowded as an Egyptian tomb,

stacked floor-

to-ceiling with hundreds of Klan-robed dolls and

effigies of all

the Klan represented: torchlight parades, strange

rituals, lynchings.

A neon cross high up on the wall presided impassively

over the

silent mayhem of the room.

I recall he also had a photograph

taken of a Klan march in Washington, D.C. in 1928.

As Andy Grundberg reminds us in his essay

in the William Christenberry volume

the contents of this Klan Room were stolen, under mysterious circumstances,

soon after we had seen it. I recall Bill telling Howard and me about the robbery,

and him describing his distress in now having to suspect everyone to whom he’d

shown it, a chosen few friends. As Andy Grundberg reminds us in his essay

in the William Christenberry volume

the contents of this Klan Room were stolen, under mysterious circumstances,

soon after we had seen it. I recall Bill telling Howard and me about the robbery,

and him describing his distress in now having to suspect everyone to whom he’d

shown it, a chosen few friends.

At a recent lecture in Los Angeles Bill revealed that during the

robbery the doors to the storeroom had evidently been taken off their hinges

and then replaced before the thief’s or thieves’ escape, which suggests a

highly focused robbery by a very professional group or individual. It is no

wonder that among the suspects were pro- or anti-clan sympathizers.

For Christenberry this more frightening side of Alabama life is

presented as another aspect of his memory, dark and horrifying memories as they

are. And, although no works from the Klan Room appear in the Smithsonian

American Museum Show, one eerily recognizes the same terrifying images in the

reverse V-shaped images of the “Dream Building Ensemble,” a suite of eleven

sculptural forms that may appear first as images similar to the Washington

Monument in D.C., but quickly transform themselves before one’s eyes into

terrifying all-white emblems of futurist-like cities akin to those of Fritz

Lang’s Metropolis or even of Ridley

Scott’s Blade Runner. Christenberry’s

drawing “Study for a Dream Building,” his variously colored sculptures

“Variations on a Theme, Eight Dream Buildings,” and is 2000 “Dream Building

(Blue)” all reiterate the same images, thus incorporating the Klan figures into

his totemistic memory as well.

A few years ago, I would have stopped this essay here,

agreeing with all of the observations—observations which include comments by

the artist himself—I’ve reiterated above. But this time, as I observed the

various photographs, paintings, sculptures and combines while discussing with

the artist and his wife the writings of James Agee and Eudora Welty (the later

of whom with Bill had a long conversation in her Jackson, Mississippi house), I

suddenly was struck by the fact that despite the great beauty and longing of

this work, it is not representative of what one might describe as a

confirmation of life. Indeed, except for a couple of early works (“Fruitstand,

Sidwalk, Memphis, Tennessee” of 1966 and the beautifully formally-constructed

[by accident Christenberry told me] photograph “Horses and Black Buildings,

Newbern, Alabama,”), Christenberry’s art was not only “bereft of human beings”

but conveys little sign of living whose lives were or are connected with his

subjects. Change, yes change is expressed everywhere: in image after image one

witnesses the transformation of buildings through time. But in most cases,

these buildings had already lost their original purposes and were left in a

state of decay or, as with the iconic Sprott Church, were transformed beyond

recognition before being caught in the shutter of Christenberry’s camera.

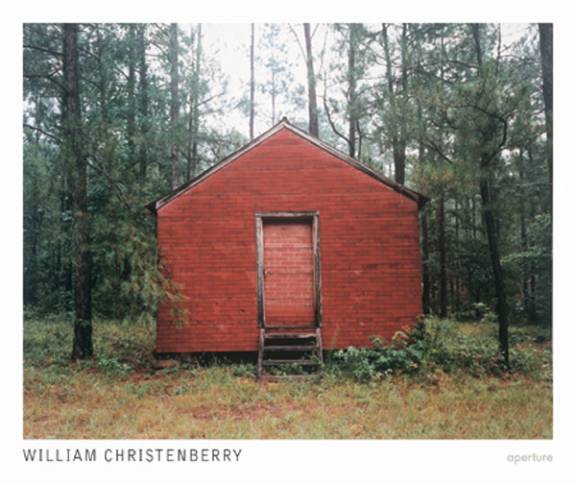

When Christenberry personally describes several of the images,

he is delighted to share the stories involved with them, revealing often

anecdotal and emotionally moving incidents that relate to the houses, barns,

warehouses, and even signs which his art has embodied. We discover, for example,

that the seemingly impenetrable “Red Building in Forest” was, in fact,

originally a small, back country school house and, later, a polling location

for people living in this removed location.

But without the background information, his images seem to

have little to do with human use, and even the artist, before his encounters

with owners and neighbors, often pondered some of these building’s

purposes. Even without the obvious

images of graves and the most recent crypt-like constructions of “Black Memory

Form” of 1998, “Memory Form with Coffin” of 2003, and “Memory For (Dark

Doorway)” of 2004, much of this art consists almost of images of the dead. Far

from being objective, “nonjudgmental” presentations of nature, the photographs

of kudzu for example (“Kudzu Devouring Building, near Greensboro, Alabama,” for

example) are quite emotionally-charged even in their titles. This world, the

world we cannot help but recognize as one with which the artist is

nearly-obsessed, is literally falling apart, being destroyed not only by nature

but by the forces—social and individual—that once controlled it. One need only

compare the various photographs and reconstructions of Sprott Church with

Agee’s description of an Alabama church to recognize that the vision with which

Agee imbues buildings and objects is not that of Christenberry’s:

It was a good enough church from the moment the curve

opened and we

saw it that I slowed a little and we kept out eyes on

it. But as we came

even with it the light so held it that it shocked us

with its goodness straight

through the body, so that at the same instant we said Jesus. I put on the

brakes and backed the car slowly, watching the light

on the building,

until we were

at the same apex, and we sat still for a couple of minutes

at least before getting out, studying in arrest what

had hit us so hard as

we slowed past its perpendicular. (Let Us Now Praise Famous Men).

If Agee’s church—not far away,

according to Christenberry, from Sprott Church—is all aglow with “goodness,”

Christenberry’s 1981 photo is set against a dark stand of woods. No doubt, if

Christenberry had photographed only that image, it might also be said to

represent “goodness straight through the body”; but in the repeated

images—whether reconstructed as sculpture or revisited as in the truncated 1990

photograph—we ultimately see this structure as a strangely lonely and isolated

thing. In the 1974-75 sculpture, wherein the church is represented as being set

up on blocks and the stairway is presented without railings so that one might

almost fear to enter—particularly in its photographic reproduction in the book,

but also in its actual dramatically lit position of isolation in the

show—Christenberry’s memory church resembles less an site which might elicit a

cry of “Jesus” than an image out of a lonely Edward Hopper landscape. Whereas

Agee’s church seems to call up “God’s mask and wooden skull and home” standing

“empty in the meditation of the sun,” Christenberry’s “house of God” calls up

something like a burial tomb, topped with majesty of two Klan like reverse

V-shaped figures. The later truncated version looks more like the “Red Building

in Forest” hut, the latter with a door so uninviting to entry that it matches

the bricklike surface of the rest of the structure. It is no accident that the

most recent “Sprott Church” is covered, like Poe’s famed house, in wax.

Again and again, not only are

Christenberry’s structures devoured by kudzu but are destroyed by time and

nature (such as “Fallen House, near Marion, Alabama” or the “Remains of Boys’

Room, near Stewart, Alabama”). The transformation of “Wood’s Radio-TV Service”

to “The Bar-B-Q Inn” ends in the vacancy of Martin Luther King Road.

Christenberry’s Alabama represents not only a world out of the past, but world

destroyed, dead, lost.

Within this context, The Klan Room and the associated images

of its undeniable evil do not appear to be so much in opposition or even in

juxtaposition to these other images, as they are at home in it, perhaps even

partially explaining why and how that Eden fell. Here, for the first time in

the artist’s oeuvre, are human

beings—and grandly dressed beings at that—but instead of bringing life to this

now empty world, they symbolize the brutal hate and death that were at the

heart of its destruction.

Christenberry’s is a world fallen, lost, yes, but also a world

once loved. And in that respect, we perceive in his obsession with his Alabama

childhood—depicted not only in his own works but in some carved wooden tools

from the museum’s vast folk-art collection, crafted by his own father—a sort of

homespun American Proust who is bent on not simply representing his own Edenic

past, but portraying a life now lost to all, an Eden wherein man was Satan

himself. Perhaps such a world was destined to be destroyed and can only now be

represented in the remnants that still exist or might be imagined in monuments

of ones own making, the only possibility left for redemption.

Los Angeles, September 4, 2006<

December 1, 2006

Copyright

©2007 by Douglas Messerli

Douglas Messerli is the editor of Green Integer and The

Green Integer Review. He is currently working on a multi-volume cultural

memoir.

|

The tour of his new show was fascinating

to me not only because I enjoy Christenberry’s art, of which this show

presented a good selection, but also because of the artist’s own observations

about his art. I recognize that most critics detest just such heavily “guided”

viewings; but I love them, if only because it is at these times when one can

truly get to know the artist—or at least get to know what the artist feels is

most important about his art. Bill is a laconic southerner, and I don’t believe

that he offered much information about his work that hasn’t previously been

published, but the tone of his

comments and the focus of his

observations were significant, if only in his reiteration of his major

concerns. What a pleasant afternoon: a guided tour by the artist followed by my

friend’s lecture!

The tour of his new show was fascinating

to me not only because I enjoy Christenberry’s art, of which this show

presented a good selection, but also because of the artist’s own observations

about his art. I recognize that most critics detest just such heavily “guided”

viewings; but I love them, if only because it is at these times when one can

truly get to know the artist—or at least get to know what the artist feels is

most important about his art. Bill is a laconic southerner, and I don’t believe

that he offered much information about his work that hasn’t previously been

published, but the tone of his

comments and the focus of his

observations were significant, if only in his reiteration of his major

concerns. What a pleasant afternoon: a guided tour by the artist followed by my

friend’s lecture!

As Andy Grundberg reminds us in his essay

in the William Christenberry volume

the contents of this Klan Room were stolen, under mysterious circumstances,

soon after we had seen it. I recall Bill telling Howard and me about the robbery,

and him describing his distress in now having to suspect everyone to whom he’d

shown it, a chosen few friends.

As Andy Grundberg reminds us in his essay

in the William Christenberry volume

the contents of this Klan Room were stolen, under mysterious circumstances,

soon after we had seen it. I recall Bill telling Howard and me about the robbery,

and him describing his distress in now having to suspect everyone to whom he’d

shown it, a chosen few friends.